Jacob told his sons:

Soon I will die, and I want you to bury me in Machpelah Cave. Abraham bought this cave as a burial place from Ephron the Hittite, and it is near the town of Mamre in Canaan. Abraham and Sarah are buried there, and so are Isaac and Rebekah. I buried Leah there too. Both the cave and the land that goes with it were bought from the Hittites.

When Jacob had finished giving these instructions to his sons, he lay down on his bed and died. Joseph started crying, then leaned over to hug and kiss his father.

Joseph gave orders for Jacob’s body to be embalmed, and it took the usual 40 days.

The Egyptians mourned 70 days for Jacob. When the time of mourning was over, Joseph said to the Egyptian leaders, “If you consider me your friend, please speak to the king for me. Just before my father died, he made me promise to bury him in his burial cave in Canaan. If the king will give me permission to go, I will come back here.”

The king answered, “Go to Canaan and keep your promise to your father.”

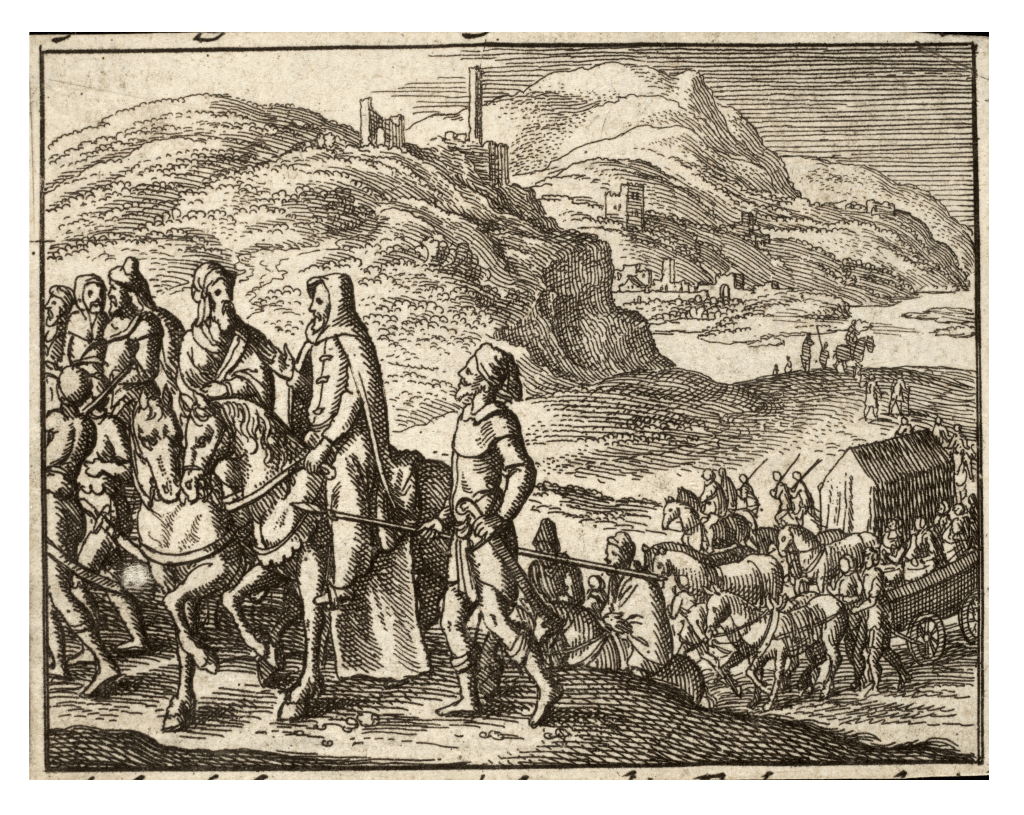

When Joseph left Goshen with his brothers, his relatives, and his father’s relatives to bury Jacob, many of the king’s highest officials and even his military chariots and cavalry went along. The Israelites left behind only their children, their cattle, and their sheep and goats.

After crossing the Jordan River, Joseph stopped at Atad’s threshing place, where they all mourned and wept seven days for Jacob. The Canaanites saw this and said, “The Egyptians are in great sorrow.” Then they named the place “Egypt in Sorrow.”

So Jacob’s sons did just as their father had instructed. They took him to Mamre in Canaan and buried him in Machpelah Cave, the burial place Abraham had bought from Ephron the Hittite.

After the funeral, Joseph, his brothers, and everyone else returned to Egypt. (Contemporary English Version)

117 days. That’s how long Jacob’s family, along with the people of Egypt, mourned for him after his death. Yes, he was a patriarch. And yes, Joseph was the administrator of an entire nation. Yet this was not unusual behavior; it was normal.

When my mother-in-law was tragically and suddenly killed in a car accident, 30 years ago, I could not take any bereavement time off, because according to company policy, it was not my mother. So, since she lived a thousand miles from us, I had to use vacation time and take a week away. Then, when I returned to work, I was expected to pick up where I left off, as if nothing had happened.

Although I work under better conditions today, and workplaces are getting better at acknowledging the importance of tragic events in the life of employees, we still have a long way to go in dealing with grief, bereavement, mourning, and lament.

The modern funeral industry is a rather recent phenomenon in history. Beginning with, and then following, the American Civil War, death was a prominent specter, affecting every community and nearly every home. People like my second great grandfather became part of a growing business of handling the dead and providing services for grieving families. He became a coffin maker and a chief supplier for the burgeoning funeral parlor (which later morphed into a furniture business which lasted a hundred years).

Even though families needed help after a devastating war, over time, the unintended effect is that we became detached from death. Others could handle bodies and arrangements. We could choose to see or not see the dead. Folks began losing the ability to grieve and mourn their changes in life.

Grief doesn’t just go away with time. If it isn’t acknowledged, faced, accepted, and dealt with, it slowly begins to sit in the soul and rot. Eventually, it becomes spiritual gangrene; the person becomes bitter, without joy and stuck in unwanted emotions.

The point of all this is that grief and bereavement strikes us all; none of us gets off planet earth without having to deal with the loss of significant people in our lives. And when it happens, it’s imperative that individuals and societal structures allow for the time and space to mourn.

The ancients were on to something which we need to recover. They discerned the importance of allowing grief to run it’s course, instead of us trying to master grief, get over it, and move on. Grief will be dealt with when it is dealt with. Trying to tame it is like attempting to bench press 700 pounds; it’s only going to crush you if you try controlling it.

I’m not agitating for a 117 span of days for everyone’s mourning. But I am insisting that we have conversations about grief and confront it, rather than ignore it. Because grieving doesn’t mean you’re imperfect; it means you’re human.

The way we move through our grief is by telling our story – which requires someone to listen. That only happens if we have created the space for it to occur. Expectations of moving-on will leave grief where it is, poisoning us from the inside-out.

The only way to the mountain is through the valley. The only way to make the pain go away is to move through it – not by avoiding it, pretending it’s not there, or trying to go around it. Pain and suffering are inevitable; misery is optional. And letting bereavement and grief have it’s way for a while is the path away from the misery.

You will heal and you will rebuild yourself around the loss you have suffered. You will be whole again, but you will never be the same. And that’s a good thing. It gives us the ability and empathy to extend blessing to others who will eventually face their own terrible loss. They will need someone to listen. And you will be there for them.

Lord, do not abandon us in our desolation. Keep us safe in the midst of trouble, and complete your purpose for us through your steadfast love and faithfulness, in Jesus Christ our Savior. Amen.